Narcos (2015-2017) - the Netflix Show's Real Life Context

In the past, I haven't been huge on foreign movies and TV shows. People had recommended Narcos (2015-2017), a Netflix original, to me before, but I hadn't paid much attention (half of it is in Spanish, and it's set mostly in Colombia. You can read more here on why Americans aren't big on subtitles, and how Narcos played a part in easing people's antipathy.) However, in college, I have been trying to expand my horizons. I studied abroad in Singapore, worked in China for a summer, took a Texts & Ideas class where I learned to read and analyze the Bible critically (I am not religious), and most recently, chose a Latin American Cultures class to fulfill my Cultures & Contexts requirement. Shoutout to my NYU professor, Patricio Navia, for involving all kinds of media in our curriculum and for reminding me to watch Narcos! This isn't so much as a TV show review, but, truly, it is beautifully filmed and performed, and I highly recommend it.

The coronavirus pandemic, the subsequent lockdown, and limited government aid will pave the way for greater inequality and retract any progress gained in the last several years. Guerrilla groups are stepping in for the government, demonstrating their influence in the regions they control. On one end, more and more social activists are being murdered, and violence against FARC has escalated. On the other, the ELN announced a unilateral ceasefire, FARC members are churning out thousands of masks and others are providing food and relief to stricken communities. Many years of inequality, drug trafficking, terrorist groups and warfare have turned Colombia into one of the most dangerous countries in the world, but it is up to the government, who has repeatedly let the country down, to end its neglect toward its citizens and start advancing toward consolidation of democracy.

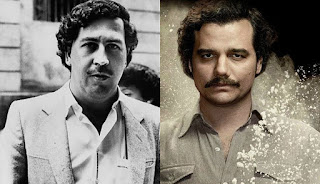

Source: All That's Interesting, 2015

The show weaves in video clips from that time period and audio narration of the historical context. During the weekend that I binged Narcos in late March after the quarantine began, I frequently paused to conduct hasty research on whether certain things really happened and on the timeline of events. I found that overall, the show was accurate in its portrayal of Pablo Escobar and the plights that afflicted the country. As Joshua Rivera for The Verge wrote in "Narcos: Mexico is a show for people who want the drug war to last forever":

There is a long series of assumptions in this, ideas that have been present in Narcos from the start, even as it occasionally paid lip service to their subversion: that Central and South American nations are lawless playgrounds for the corrupt, where prosperity can only be seized by crooks and violence reigns. Every now and then Narcos does its diligence to complicate this picture, almost entirely via narration: a tossed off line that notes the Mexican and Colombian drug trades exist wholly to serve the appetites of the wealthy in the US and Europe, or another about the fundamentally destabilizing influence of the United States’ foreign policy that created problems in exchange for the glow up of “solving” them.

Long after I finished binging both shows, the question of really, how did the drug war come to be, and why is it so challenging to end it? The U.S. evidently plays a role, not just as a buyer of drugs, while the struggle for the Latin American economies to stand unsupported appeared to be both a cause and effect. I knew that for my Latin American Cultures final exam, I wanted to dive deeper into how the issues of civil war, guerrilla warfare, drug trafficking and persistent inequality have prevented democracy from consolidating in Colombia.

I will start by bringing up the 2016 peace deal, which ended the 52-year civil war in Colombia between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian government. It symbolized the end of decades-long violence and hope for a renewed democracy, yet fast forward to 2019--and still ongoing--in which Colombians have erupted in a flurry of protests that see a cross pollination of issues, bringing together the indigenous peoples, university students, Afro-Colombians, feminists, cultural figures, etc. The rise in dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of numerous issues is a continuation of the many problems that have plagued Colombia—civil war, guerrilla warfare, drug trafficking and persistent inequality.

Colombia is no stranger to violence, even before this civil war. In the transition from the 19th to the 20th century, it experienced “The War of the Thousand Days,” and then in the mid-1900s, a ten-year civil war, both of which were caused by hatred between the Liberal and Conservative parties. The National Front was eventually formed to prevent partisan violence and to facilitate the transition to civilian rule. However, during the civil war, the Liberal party had backed the formation of a few guerrilla groups, but excluded them, as well as other leaders, in the central government. The lack of democratic competition and persistence of inequality “sowed the seeds for future conflict” and set Colombia up as a battleground for class differences and the creation of various guerrilla groups.

Tensions amongst major armed groups, dominated by the aforementioned FARC, National Liberation Army (ELN), United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC), and Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and with Colombia’s armed forces have prevented democracy from consolidating. The conflicts resulted in over 200,000 deaths, most of them civilians, and around 6,000,000 people displaced. For many years, the government has struggled to curtail the bloodshed, through countless ceasefires, peace talks, and amnesties, much to no avail. This may be in part due to its frequently contradictory behavior, either by contributing more to the violence or ignoring criminal acts taking place. Instead of protecting its citizens and supporting their rights, authorities might search through media offices and exert heavy-handed military tactics even against peaceful protests. Paramilitary groups and rebels would also target leaders of grass-roots social movements; combined with government defamation of protesters as “fronting for guerrilla groups and foreign leftist regimes,” protests remained sporadic and low in number up until recently, as Silvia Otero Bahamon and Sandra Botero wrote in The Washington Post. In one case study, the ELN thought that by “upping their terrorist attacks [sic] by being more defiant, they could somehow could gain more political ground,” a method which has served certain criminals like Pablo Escobar; on the contrary, it caused further stigmatization, leading a Colombian army official to kill a government-funded bodyguard and wound a social movement leader. The politicians who run for office to make a change are often assassinated, while many others have ties to paramilitary groups or take bribes from drug cartels. In an ironic turn of events, after repeated failures to reach an agreement, former President Uribe even proposed to pay ELN guerrillas to stop kidnapping. Instead of a democracy, Colombia has adopted more of a “paternalistic” form of governing, controlled by the criminals and the elites.

The fragility of Colombia’s democracy is largely a result of the government’s inability to follow through with its plans, one reason being the history of elitism and oligarchy within the government. The gains from economic development don’t reach the lower levels of society, who experience poverty and limited access to basic needs; in fact, on land sold to multinationals and used for mining, the local population suffer the consequences of contaminated water and air pollution. When fights between the armed groups and the government left devastation and other collateral damage across rural areas, no aid was given. Perhaps the most salient example is the 2016 peace deal; indigenous groups, who live on 30% of the most affected land zones, were not invited to peace talks. Additionally, though nearly all of the rural population voted yes in the peace referendum, the deal didn’t pass at first due to the marginally greater number of “no” votes by the city habitants. The key points of discussion in the 2016 peace deal—land reform, political participation, disarmament of the rebels, drug trafficking, the rights of victims, and the implementation of the peace deal—with the FARC and M-19’s transition from guerrilla group to political party in 1990 signify the left-wing groups’ desires to shape the discourse and institute meaningful reform. Three years later, the rural regions most affected by the war have seen little investment, with excuses made that “given the scale of the task and the level of damage that some areas suffered during the conflict, accomplishing even basic development promises tied to the peace deal…will take upwards of a decade." These dashed hopes and negative sentiment extend to President Duque, who comes from an elite background, supports landowners and recently “called for a national dialogue about critical issues, but with no clear plans to involve ordinary citizens,” from reporting done by Bahamon and Botero. In the meantime, more criminal gangs have emerged, simply moving into formerly FARC-controlled areas, and illicit drug production has skyrocketed.

Within these conflicts and as a result of them, drug trafficking has flourished in the last few decades. Its hand in violence ranges from fighting over cocaine production and distribution routes to killing political opponents to exacting vengeance. Though the initial purpose was not to deal drugs, according to Pablo Medina Uribe's article in AS/COA, many groups “struck deals with narcos to protect mutual interests…and to protect coca crops,” finance their operations, bribe politicians and buy votes. Inequality and the drug trade are also understandably intertwined. The short story is that coca plants, which provide the key component of cocaine, are extremely lucrative. In government attempts to derail cocaine production, it has burned plantations down or offered subsidies and productive infrastructure programs for more costly, legal crops. In the former scenario, many farmers have lost the knowhow of planting other crops, such as cattle and coffee, leading them right back to coca. In the latter, the infrastructure projects, which were supposed to help rural economies reach other ones, were not delivered even in the pilot towns and the crop-substitution payments halted briefly once Duque took office and the alternative crops never arrived. The power to feed illegal economies and exert control over the land bring about continued perversion of democracy and justice, but the lack of dedicated government support has just as much contributed to the disorder in Colombia.

The coronavirus pandemic, the subsequent lockdown, and limited government aid will pave the way for greater inequality and retract any progress gained in the last several years. Guerrilla groups are stepping in for the government, demonstrating their influence in the regions they control. On one end, more and more social activists are being murdered, and violence against FARC has escalated. On the other, the ELN announced a unilateral ceasefire, FARC members are churning out thousands of masks and others are providing food and relief to stricken communities. Many years of inequality, drug trafficking, terrorist groups and warfare have turned Colombia into one of the most dangerous countries in the world, but it is up to the government, who has repeatedly let the country down, to end its neglect toward its citizens and start advancing toward consolidation of democracy.

Comments

Post a Comment